A few weeks ago I published a compendium of over 370 creatures in Philippine Mythology. A week later, I published a chart that outlines the gods and monsters and the regions they come from. A question that kept popping up on social media was, “why are there so many?” So I decided it was time to get my ass in gear and finish up an article I have been working on which outlines the how and why of Philippine Mythology. The following three articles are a compilation of what I have learned while being a Philippine Mythology enthusiast. It is open for debate and discussion and is by no means the final word on the subject. Migration routes have not been set in stone, therefore neither can the understanding of Philippine beliefs.

The theories on how the Philippines was populated is of constant debate. DNA tests, language studies, and cultural practices have long been evaluated in search of answers. As these studies progress, the understanding of Philippine mythology and early beliefs also becomes easier to map out. Most people who become interested in Philippine Mythology (and the current beliefs of the indigenous populations) quickly get overwhelmed with the hundreds of names and descriptions of supernatural beings. In reality, there are not that many core creatures, but there are dozens of ethnolinguistic groups and regionalized descriptions – which resulted in different names for them. There is also the issue of migration patterns. In general, beliefs dissipated as they moved from South to North – and more recently, North to South.

The evolution of beliefs in the Philippines had eight waves of influence.

- Negrito Tribes

- Out of Sundaland Model

- Austronesian Expansion

- Indianized Kingdoms

- Sinified States

- Muslim States

- Christianity

- Westernization

Before we begin, I feel I should mention that scientists recently excavated an archaeological site on the island of Luzon in the Philippines. The excavations, which were in the Kalinga province, uncovered 400 animal bones and 57 stone tools. Researchers determined that the bones belonged to a deer, freshwater turtles, and stegodons. Along with the recently discovered bones was 75 percent of a fossilized skeleton of a slaughtered rhinoceros. There were also several cuts on the skeleton.

Using electron spin resonance, the researchers determined that the rhinoceros was killed 709,000 years ago. Since the researchers believed that a human killed the rhinoceros, this means humans were in the Philippines at the same time. These early inhabitants do not have any known effect on the evolution of Philippine Mythology, but it is still a very exciting discovery.

Although it was determined that humans did live in the Philippines over 700,000 years ago, there is still some uncertainty regarding which species of humans inhabited the land.

Early Animism:

In its simplest definition, Animism is the belief in innumerable spiritual beings concerned with human affairs and capable of helping or harming human interests. They could be addressed in particular objects, such as stones or posts, which some early peoples would set up in likely places. The few personally venerated spirits (or gods) were identified with thunder, sun, moon, hunting, childbirth, and the winds. Evil spirits might be incarnate in animal or monstrous forms and could cause disease or other misfortune. This was not unique to the Philippines, but is a common trait among most animism belief structures throughout the world.

Negrito Tribes:

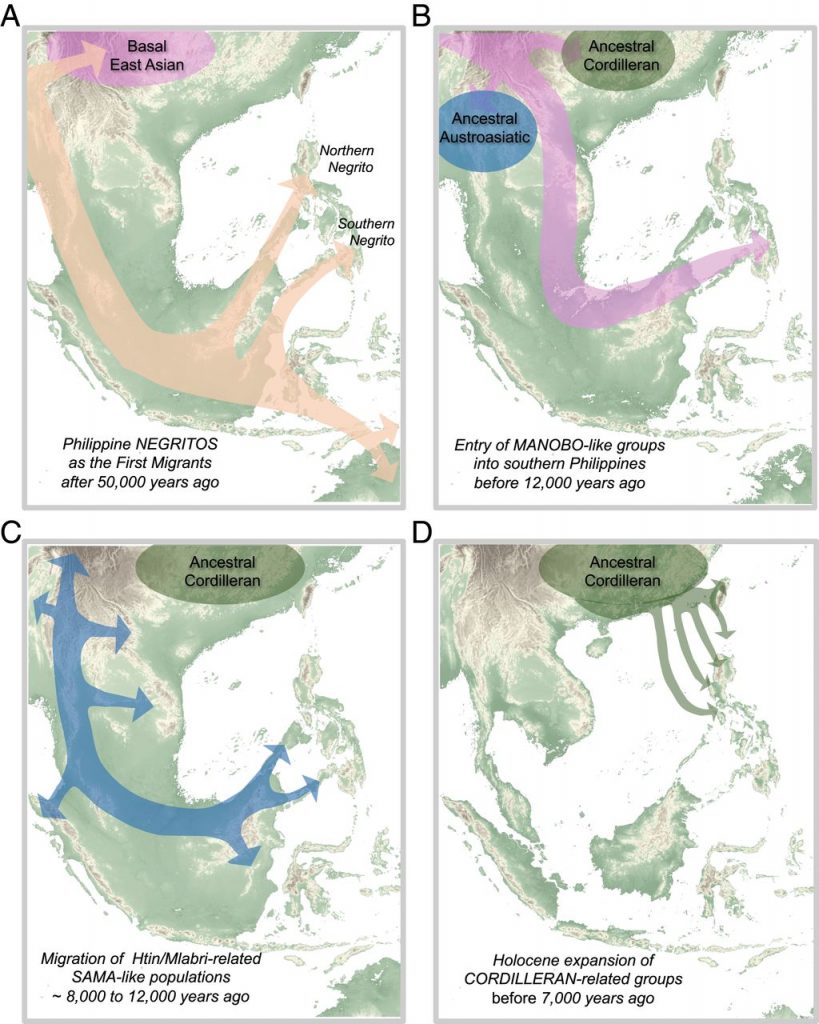

It is known that the first inhabitants of the Philippines were the negrito tribes, or Aeta. Some new evidence shows that the migration from Africa to Southeast Asia and Australia might have occurred between 80,000 and 120,000 years ago. The migration routes from Africa to Southeast Asia were rather multiple and along the way of migration, the H. sapiens interbred with other species like Neanderthals, Denisovans and Homo erectus. David Reich of Harvard University, in collaboration with Mark Stoneking of the Planck Institute team, found genetic evidence that Denisovan ancestry is shared by Melanesians, Australian Aborigines, and smaller scattered groups of people in Southeast Asia, such as the Mamanwa, a Negrito people in the Philippines.

If we look at an earlier part of the the migration group in Southeast Asian, we find the Semang people of Malaysia. The traditional religious beliefs of the Semang are complex. They include many different deities. Most of the Semang tribes are animistic. They believe that non-human objects have spirits. Many important events in their lives such as birth, illness, death and agricultural rituals have much animistic symbolism. Their priests practice magic, foresee the future, and cure illness. They would use Capnomancy (divination by smoke) to determine whether a camp is safe for the night. Their priests are said to be “shaman” in that they are someone who acts as a medium between the visible world and an invisible spirit world. The Semang bury their dead simply, and place food and drink in the grave.

You’ll find similar beliefs among all the animist tribes from this migration, but it seems to have become “darker” in environments which were harsher. It also seemed to become less complex as the migration moved northward in the Philippines.

Negrito beliefs in the Philippines regarding these spirits are described as such ” Colonial and even pre-colonial accounts describe the Ati as having no God or gods, but a series of spirits, called talunanon which they placate to ensure an easy existence (Carreon, 1943: pp.6, 8). Talunanon are believed to inhabit sacred trees, springs and other significant features of the natural environment, all of which are treated with the utmost respect. Behaviors of speech, thought and action are restricted in such holy places in order to honor or pacify the talunanon, and to maintain balance between the Ati world and that of the spirits.”

Talunanon are not necessarily benevolent and can be the cause of physical and psychological/psychic diseases. A person who falls ill is asked by the healers to retrace her steps to the place where she began to feel unlike herself or to recount her actions to a similar point in time. The talunanon of that place is then given food and other ritual offerings to release the sick person’s affliction.

NOTE: The belief in malevolent spirits were part of the earliest animist societies throughout SE Asia. No evidence of witchcraft being performed in the Philippines during this period has been confirmed.

THE “OUT OF SUNDALAND” MODEL: 15,000 to 7,000 years ago

A study from Leeds University and published in Molecular Biology and Evolution, examining mitochondrial DNA lineages, suggested that humans had been occupying the islands of Southeast Asia for a longer period than previously believed. Population dispersals seem to have occurred at the same time as sea levels rose, which may have resulted in migrations from the Philippine Islands to as far north as Taiwan within the last 10,000 years – the “Out of Sundaland” Model. Earlier animist beliefs developed dramatically over this time and began including more complex ancestor worship. The earliest ancestors of an ethnic lineage were often represented as animals and spirits, or associated to them. This form of animism also believed in more complex “deities” which one could only communicate with through “lower spirits”. These beings mediated between man and the higher spirits/ deities, but must first be paid homage. Deities/ spirits possessed specific powers and were localized to a geographical area. The deities/spirits inhabited places such as rivers, mountains, forests, oceans, etc. Some deities exercised power over human affairs (business, marriage, death, etc.) other gods exercised powers over nature (storms, rain, etc.)

By the time this migration happened, all sorts of ghouls had been incorporated into Austronesian folk beliefs. A few examples are as follows:

- Bajang: the spirit of a stillborn child in the form of a civet cat (musang).

- Bota: a type of evil spirit, usually a giant

- Jembalang: a demon or evil spirit that usually brings disease

- Lang suir: the mother of a pontianak. Able to take the form of an owl with long talons, and attacks pregnant women out of jealousy

- Mambang: animistic spirits of various natural phenomena

- Penanggal: a flying head with its disembodied stomach sac dangling below. Sucks the blood of infants.

- Penunggu: tutelary spirits of particular places such as caves, forests and mountains.

- Raksaksa: humanoid man-eating demons. Often able to change their appearance at will.

- Toyol: the spirit of a stillborn child, appears as a naked baby or toddler

The Filipino counterparts are obvious – Tiyanak, Aswang, Manananggal, plus various shape-shifters and dark beings. The belief in these being dissipated as the migration moved north in the Philippines. The “Sundaland” theory makes sense when studying Philippine Mythology. As we move South to North in the Philippines, the animist beliefs in ghouls become more diluted.

In the Southern Philippines, where the migrations may have been at their strongest, belief in ghouls became widespread. For instance, among the Bagobo Tribe they have:

- Buso – Evil spirits who eat dead people and have some power to injure the living. A young Bagobo described his idea of a buso as follows:“He has a long body, long feet and neck, curly hair, and black face, flat nose, and one big red or yellow eye. He has big feet and fingers, but small arms, and his two big teeth are long and pointed. Like a dog he goes about eating anything, even dead persons.”

- Tagamaling (a type of buso) – A cannibalistic creature that is kind to humans one month but eats them on the next month.

- Tigbanua (A type of Buso) – These beings are the most feared of the Buso since, not content with digging up corpses, they are forever trying to kill live.

Later Austronesian influences also introduced the concept of shamans invoking spirits for benevolent or nefarious purposes. Shamans (known in Malay as dukun or bomoh) are said to be able to make use of spirits and demons for either benign or evil purposes. Although Western literature may compare this to the familiar spirits of English witchcraft, it actually corresponds more closely with the Japanese inugami and other types of shikigami, in that the spirits are hereditary and passed down through families.

It is also interesting to see some of the superstitions that may have developed in Malaysia and were brought by this dispersal. To this day, old folks in Malaysia will advise you to say “Excuse Me” before you pee in the jungle, though there is nobody around. This is to inform the “invisible” entity to give way, so you won’t pee on them. Sounds very similar to the superstition around saying “tabi-po” for the same reasons.

NOTE: The Sundaland migration is important because it developed the core of the supernatural beliefs in the Philippines. Regardless of what came after this, this core belief in ghouls remained relatively unchanged. This migration also expanded the ideas of potions and other herbal concoctions to induce love, cast spells, and also to heal. The Austronesian Expansion could also explain why these beliefs did not take root in the Northern Philippines.

AUSTRONESIAN EXPANSION – 5000 years ago

Recent evidence shows the Austronesian Expansion wasn’t nearly as large as first thought. The science behind the Sundaland Theory certainly gives good cause to challenge it. On Taiwan, the Austronesian speaking fishermen-farmers honed their sea-faring skills. They soon embarked on what is known as the Austronesian expansion. By about 2,500 BCE, one group, and just one group of Austronesian speakers from Taiwan had ventured to northern Luzon in the Philippines and settled there. The archaeological record from the Cagayan Valley in northern Luzon shows that they brought with them the same set of stone tools and pottery they had in Taiwan. The descendants of this group spread their beliefs in totemism as well as the other cultural and technological advancements they had developed. As the expansion moved southwards in the Philippines, the belief in totemism dissipated. It is unknown whether this totemsim first developed on the Indo China mainland or not. We do know that, in other areas, totemism grew as it moved further away from the center of the Sundaland migration. This can be seen in Hawaii, Easter Island, and tribes in the Americas.

Examples of these beliefs can be seen in studies of the Igorot people. It was also intertwined with the foundations of what would become the beliefs structures of the Early Tagalogs and Visayans. It is not immediately recognizable in folk beliefs on Taiwan and in China because they were eventually incorporated into Taosim and the other beliefs that followed, such as Buddhism. We do know that ancestor worship became a huge part of those.

NOTE: This migration potentially introduced totemism to the Philippines. The Sundaland Model and The Austronesian Expansion could be a small part of why there are so many obvious differences between indigenous beliefs in the North and South. The Southern part of the Philippines were likely influenced strongly by the animist beliefs from an earlier Sundaland migration, while the Northern part of the Philippines saw stronger influence from the Austronesian expansion. The base of similarities can be seen in the early “out of Africa” tribes.

Particularism:

One characteristic of all animistic religions is their particularism, a quality opposite to the universalism of the larger “world religions”. Animist beliefs were specific to groups and even individuals. This is why there is so much difficulty in understanding pre-Christian beliefs in the Philippines. There is no blanket understanding of what it was. It literally needs to be examined region by region. This is why many tribes and ethnic groups in the Philippines have their own creation story and their own name for most deities or malevolent spirit. It is also why so many share similarities. In the central and southern Philippines, every region also created their own name and regional characteristics for the ghouls. This is essentially why you have so many gods and creatures in Philippine Mythology. If you break it down by region, and migration, it isn’t quite so overwhelming.

CONTINUE READING: INDIANIZED KINGDOMS | Understanding Philippine Mythology (Part 2 of 3)

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.