|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

When we talk about Philippine folk beliefs, we usually refer to the ghost stories of our elders. We might share stories about how an engkanto fell in love with our tita and got her sick, or how a duwende in our lolo’s house keeps hiding his things. My own grandfather calls them his playmates–after a long search around the house, he’d find the items where he started looking. At times, when he’d get frustrated he’d just command them to return it–and they would. These stories are old; they are charming, yes, but precisely because they’re distant. They hold no real threat to us.

More and more places in the Philippines are becoming urban developments. Trees are being cut down and mountains are being carved out. It seems as though the old spirits are being displaced. Long ago, they struck terror in the hearts of folks in the barrio. They lived in the shadows of thick forests and ate the liver of anyone who gets lost. They used to kidnap young women and devour misbehaving children. Today, these stories might feel childish, and useful only in the creative fields of fiction and art. But actually, the terrifying beings of folklore never left. The old forests had their own dangers: snakes and engkantos. The cities have new dangers: exploitation, class divide, and ennui.

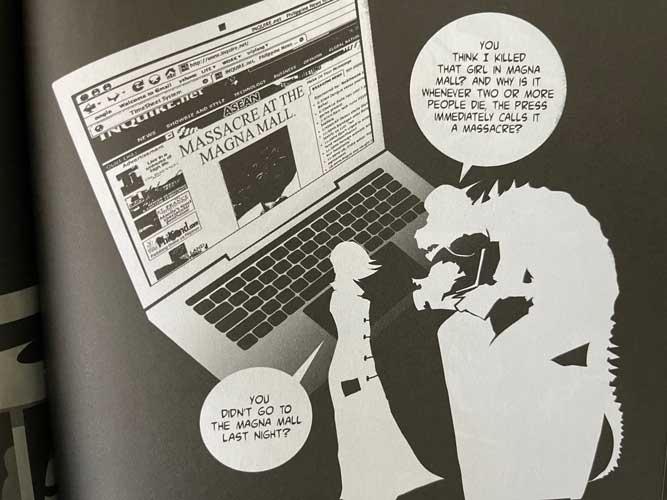

In Eugene Y. Evasco’s paper, Sa Pusod ng Lungsod: Mga Alamat, Mga Kababalaghan Bilang Mitolohiyang Urban, various mysteries of the city are listed, and their potential psychological meanings are discussed. Urban legends are new folktales. The old beings of folklore expressed the real psychic concerns of our elders. Engkantos, who were often depicted as Caucasians, may have expressed our fascination and fear with regard to our colonizers. Asking for permission before crossing duwende territory may reflect our spiritual relationship with nature. In the city, the aswang and tiyanak are still present, but they take on new meaning. When crime is blamed on aswang, it may be reflective of the inhuman nature of criminality and the monstrosity of violence. In the old stories, aswangs were shape-shifting magicians–and this may represent a mistrust of strangers, since you can’t ever know who might actually be an aswang. Today, they’re criminals. The tiyanak, which are monster babies, may represent our attitudes to abortion. Abortion is illegal in the Philippines and so many young people who seek to terminate an unwanted pregnancy might look for sketchy and life-threatening alternatives. The white ladies that haunt lonely streets may reflect how women are treated in the city, being that they are usually victims of violence. You might also remember the snake monster that lives in the basement of a popular mall, waiting for people to fall through a trapdoor in the fitting rooms. This might then represent our distrust of mall culture and mindless consumerism. There are barely any public spaces in the city, and so people spend most of their time cooling off in malls. Although you can waste an afternoon wandering around maze-like malls (tales of getting lost in local malls are not uncommon), you are encouraged, and usually forced, to spend. Understanding the psychic significance of urban folklore gives us an insight into our attitudes to the city. Interestingly, you might also recognize some of these urban folktales portrayed wonderfully in the Trese comics series.

The city also has other strange forces. Ancient trees in the city, with their thick roots breaking through the concrete, are still powerful. Children are still told not to point at them, and bite their finger in case they do. When building a house, rituals are done to appease the spirit of nature before cutting down these trees. Otherwise, we would have to build around them. There are also places in the city that hold the horrible memories of war. You might hear soldiers marching. You might also hear the disembodied screams of victims of war. Evasco also describes an oppressive air enveloping the city, built on the anxiety of modern rush and the alienation of exploitative industry. Some buildings might have stories of unfortunate people who fatally harm themselves in these cramped spaces, forever haunting these grounds.

Stories evolve, and folklore has always been an expression of human needs and fears. They are not stuck in time–they have modern applications. We like to think that the era of folklore is gone, and that we are living in a time devoid of magic. But these stories are still being developed, taking on new meaning to better suit the spirit of the modern Filipino. Our new folklorists are comic book authors and artists, writers of speculative fiction and mythic narratives, and scriptwriters and moviemakers–all of them depict our folklore in new and exciting ways, building on old stories or deconstructing them. Living in the city has its own magnificent horrors.

Carl Lorenz Cervantes is a writer and researcher. His essays have been published in academic journals, magazines, and online platforms. He finished his masters in counseling psychology at Ateneo de Manila University, and his thesis, which was published in an international journal, was on telepathy. He is currently a lecturer in the University of the Philippines in Diliman, Quezon City. He handles Sikodiwa on Instagram, where he shares his research into folklore and Sikolohiyang Pilipino (Philippine psychology).

To purchase his digital zines, click here. To listen to his podcast, click here. To follow his blog and receive articles through email, click here. To read his other writing, click here.