Philippine Studies 28 ( 1980): 142-75

Filipino Class Structure in the Sixteenth Century

WILLIAM HENRY SCOTT

This paper offers summary results of a study of sixteenth century Filipino class structure insofar as it can be reconstructed from the data preserved in contemporary Spanish sources. The major accounts on which it is based have been available in English since the publication of the Blair and Robertson translations early in the 20th century, and have recently been made accessible to the general Filipino reading public by F. Landa Jocano in a convenient and inexpensive volume entitled The Philippines at the Spanish Contact. At least four of these accounts were written for the specific purpose of analyzing Filipino society so that colonial administrators could make use of indigenous institutions to govern their new subjects. Yet any history teacher who has tried to use them to extract even such simple details as the rights and duties of each social class, for purposes of his own understanding and his students’ edification, know how frustrating the exercise can be.

The problems are many. The accounts were not, of course, written by social scientists and are therefore understandably disorderly, imprecise, and even contradictory. They do not, for example, distinguish legislative, judicial, and executive functions in native governments, nor do they even indicate whether datu is a social class or a political office. On one page they tell us that a ruling chief has life-and-death authority over his subjects, but on the next, that these subjects wander off to join some other chief if they feel like it. They describe a second social class as “freemen – neither rich nor poor” as if liberty were an economic attribute, while one account calls them “plebeians” and another “gentlemen and cavaliers.” The maharlika, whom the modern Filipino knows as “noblemen,” show up as oarsmen rowing their masters boats or field-hands harvesting his crops. And a third category called “slaves” everybody agrees are not slaves at all; yet they may be captured in raids, bought and sold in domestic and foreign markets, or sacrificed alive at their master’s funeral. Moreover, if the data as recorded in the original documents are confusing, they are made even more so by the need to translate sixteenth century Spanish terms which have no equivalent in modern English. Thus pechero becomes “commoner” and loses its significance as somebody who renders feudal dues.

It was a decade of frustrating attempts to resolve such contradictions that inspired the present study. Basic documents used for the study were:

- Miguel de Loarca’s Relacion de las Islas Filipinas (1582);

- Juan de Plasencia’s Relacion de las costumbres que los indios se han tener en estas islas and Instrucción de las costumbres que antiguamente tenian los naturales de la Pampanga en sus Pleitos (1589);

- Pedro Chirino’s Relacion de las Islas Filipinas (1604);

- chapter eight of Antonio de Morga’s Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas;

- the anonymous late sixteenth century Boxer manuscript;

- and the unpublished Historia de las Islas e Indios de las Bisayas (1688) of Francisco Alcina.

The goal of this study was to discover a distinct, non-contradictory, and functional meaning for each Filipino term used in the Spanish accounts.

VISAYAS

Both Loarca and the author of the Boxer manuscript record a Visayan cosmogony which divides mankind into five types or species: datus, timawas, oripun, negroes, and overseas aliens. The myth presents them all as offspring of a divine primordial pair who flee or hide from their father’s wrath. According to the Boxer version:

They scattered where best they could, many going out of their father’s house; and others stayed in the main sala, and others hid in the walls of the house itself, and others went into the kitchen and hid among the pots and stove. So, these Visayans say, from these who went into the inner rooms of the house come the lords and chiefs they have among them now, who give them orders and whom they respect and obey and who among them are like our titled lords in Spain; they call them datos in their language. From those who remained in the main sala of the house come the knights and hidalgos among them, inasmuch as these are free and do not pay anything at all; these they call timaguas in their language. From those who got behind the walls of the house, they say, come those considered slaves, whom they call oripes in their language. Those who went into the kitchen and hid in the stove and among the pots they say are the negroes, claiming that all the negroes there are in the hills of the Philippine Islands of the West come from them. And from the other tribes there are in the world, saying that these were many and that they went to many and diverse places.

The details of the myth are revealing of Filipino views of their own social hierarchy: class distinctions are presented as being of the same order as racial differences. The ruling class is secluded and protected in the inner security of the house (“lo mas escon dido de las casa”), Loarca says, with their privileged timawa retinue standing between them and the world in the front sala (“mas afuera”), and their more timid oripun supporters occupying the very walls of the house. And, completely beyond the pale of Philippine society, are the soot-colored negroes of the hills, and such literally outlandish races as the Spaniards themselves, descendants of those who “left by the same door through which their father had entered, and went toward the sea.” Equally significant is something the myth does not say: it fails to distinguish the rice and cotton-producing Filipinos of the uplands from those along the coast who supply them with salt, fish, and imported trade porcelains.

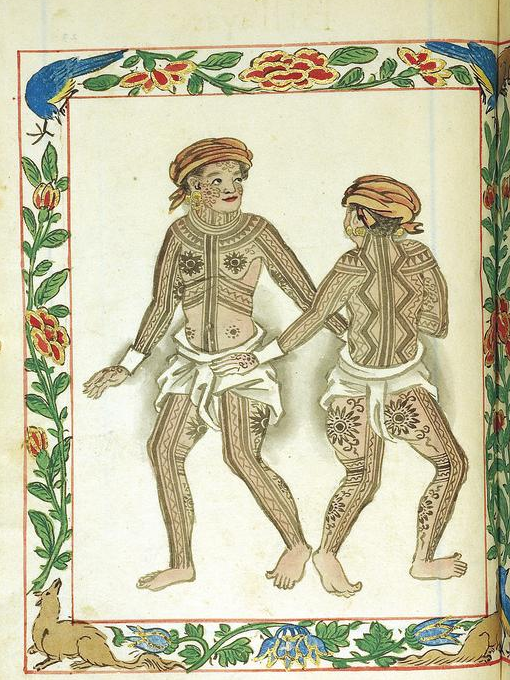

Sixteenth century Visayans therefore saw themselves as divided into three divinely sanctioned orders: datu. timawa, and oripun. The word datu is used as both a social class and a political title: the class is a birthright aristocracy or royalty careful to preserve its pedigree, and the office is the captaincy of a band of warrior supporters bound by voluntary oath of allegiance and entitled to defense and revenge at their captain’s personal risk. These supporters are timawa, and they are not only their datu’s comrades-at-arms and personal bodyguards, testing his wine for poison before he or any other datu drinks it, but usually his own relatives or even his natural sons. Everybody else is oripun. They support timawa and datu alike with obligatory agricultural and industrial labor, or its equivalence in rice. When the Spaniards reached Cebu, they found the subordination of the oripun to the other two orders so obvious and the distinction between datu and timawa so slight, that they did not at first recognize the existence of three orders. Legazpi, after three busy years of conquering, cajoling and coopting them, thought there were only two orders of Pintados: rulers and ruled. And a half century later, old Samarefios recalled the timawa as a lower order of datus, and even an extinct class in between called tumao.

THE FIRST ORDER

Members of the datu class enjoy ascribed right to respect, obedience, and support from their oripun followers and acquired right to the same advantages from their legal timawa. In theory at least, they can dispose of their followers’ persons, houses, and property, and do in fact take possession of them at their death. Land use and disposition are not mentioned in any of the accounts, presumably because Visayan sustenance comes exclusively from swiddens, forests, or the sea. Since the sons of a ruling datu have equal claim to succession, competition is keen among them, and official datu wives practice abortion to limit such divisive possibilities to only two or three offspring. Significantly, a myth recorded by Loarca attributes the invention of weapons and introduction of warfare to a quarrel over inheritance. In fact, it is normal for a datu’s brother to separate from him and form another settlement with a following of his own. To maintain the purity of their line, datus marry only among their kind, often seeking high-ranking brides in other communities, abducting them, or contracting bride prices running to five or six hundred pesos in gold, slaves, and jewelry. Meanwhile they keep their own marriageable daughters secluded as binokot. literally, “wrapped up.” Social distance is maintained by such deference as addressing them in the third person, keeping off the noisy bamboo-slatted floor while they are sleeping, or the strict observance of their mourning taboos by the whole community. Furthermore, competition from bold and wealthy kin is discouraged by such protocol sanctions as restricting the size and ostentation of their houses.

Datus of pure descent (for example, potli nga datu or tubas nga datu. or the four-generation lubus nga datu) also recognize another lineage of lesser nobility called tumao. Literally, tumao means “to be a man,” that is, without taint of slavery, servitude, or witchcraft. These are the descendants of other or former datus, or of an immigrating datu’s original comrades, or the kin of a prominent local ruler (“señor y dueño del pueblo”). From this tumao rank come a ruling datu’s personal officers, such as his Atobang sa Datu (Prime Minister), and from their sons come a corps of Sandig sa Datu (“Supporters of the Datu”), though after fifty years of Spanish occupation both the titles and offices had disappeared. Datus also maintain sandil concubines, some of them binokot (“princesses”) of high rank captured in raids, who bear them illegitimate offspring with no inheritance rights beyond their father’s favors while alive, but who are usually set free upon his death. These are the timawa, whom the origin myth considers a separate order of men, but whose descendants were fondly respected as a third grade of the first order long after colonial rule had rendered all such distinctions meaningless. Those timawa who are released on their father’s death – slaves freed from above, so to speak – are called by the special title, ginoo. By Alcina’s day, however, the term timawa alone survived as a designation for the ordinary Visayan tribute-payer who was neither chief nor slave, while ginoo took on the general Tagalog significance of “sir” because of Manila’s new prestige as the colonial capital.

Datu’s Duties and Functions. The following which a datu rules is his sakop, haop, or dolohan – what is elsewhere called a barrio or barangay, and what Alcina translates as “gathering” or “kin” (i.e., junta, congregación, or parentela ). The office or estate of datuship is therefore a ginaopan or gindolohanan. The visible house cluster of such a group is commonly called a gamoro, but like two other terms for village or settlement, lonsor and bongto, the word originally referred to a collection of people, not houses. The Boxer manuscript states that such followers obey their datus because “most of them are their slaves, and those in the settlement who are not are the relatives of the datus.” In the event of a datu’s capture in war, these relatives contribute to his ransom in proportion to the closeness of their kinship. Some datus can raise fighting forces of between 500 and 1 ,000 men-at-arms, either through confederation with other datus, or by actual overlordship (senorto ). Si Dumager of Langigey, Bantayan, for example, imposed a 20 percent inheritance tax on slaves and other property after such a conquest, a form of servitude (esclavonia) which, Loarca reports, “is still being introduced among all the Filipinos along the coast, though not the uplanders.” If any of these super-baranganic chieftains were ever dignified with the title of hadi (king), none of the accounts record it. Quite the opposite. Alcina comments scornfully of a legendary Visayan hero named Bohato: “he conquered so many ‘kings,’ as they are wont to call them around here, who were nothing more than some gang leaders not even deserving the name of captain.”

A ruling datu has the duty to execute judicial decisions handed down by experts in custom law, which execution among his peers is likely to institute a family feud. All crimes are punishable by fines, even murder, adultery, and insubordination to datus, though these latter three are technically capital offenses commuted on appeal to enslavement or servitude which is both negotiable and transferable to kin and offspring. Petty larceny (reckoned at less than ₱20) and other civil offenses are not transferable except that children born during the period of bondage become the property of the creditor. Grand larceny, however, is a capital offense, and datus themselves are liable to prosecution – though, of course, they can afford the fines or wergeld necessary to avoid slavery in any case. Where a datu’s own honor or interests are involved, he acts both as judge and executioner, and may abuse this position to procure additional indentured or slave labor by outright perversion of justice.

The datu’s main function is to lead in war. Warfare – mangubat in general, mangayaw by sea, and magahat by land – appears as endemic in all the accounts. It takes the form of raiding, trading, or a combination of both, and is terminated or interrupted by blood compacts between individuals or whole gamoros. Slaving is so common everybody knows the proper behavior patterns. A captured datu is treated with respect and his ransom underwritten by some benefactor who will realize a 100 percent profit on the investment. Men who surrender may not be killed, and the weak and effeminate are handled gently; a timawa who kills a captive already seized must reimburse his datu. A commanding datu rewards his crewmen at his own discretion, but otherwise has full rights to profit and booty. In the event of a combined fleet, the datu who provides the predeparture sacrifices to ancestral spirits and war deities receives half the total take. Visayan men-of-war are highly refined specimens of marine architecture which call for considerable capital investment to construct, outfit, and operate, and are launched over the bodies of slave victims. If a silent partner invests in such a venture, he receives half the profits but no interest on his capital. And, in recognition of the risks involved, he must ransom his active partner in the event of capture, without claim to reimbursement or return on his original investment.

Datu’s Commercial Interests. The Loarca account is full of indirect testimony to a datu’s commercial interests. Coastal Visayans barter cotton from uplanders for marine products and Chinese porcelains, and datus let out the cotton in the boll to the wives of their oripun to return as spun thread. It will be recalled that medieval Chinese accounts list cotton and porcelain as exchange goods in their Philippine trade, which was conducted from deep draft, sea-going junks and anchored off shores whose natives handled local collection and distribution. It may also be recalled that when Magellan opened a store in Cebu, his customers paid for their purchases with gold weighed out in scales carried for the purpose, as Igorots in the Baguio mine fields were still doing three centuries later. Many social customs appear to favor the pursuit of business too. Although betrayal of visitors from allied communities is a just cause for war, outstanding debts can be collected by force in such settlements without danger of war simply by seizing the sum from any of the debtor’s townmates, who will then be entitled to collect twice the amount from the debtor himself. And in contrast to loans of palay, which carry an interest rate of 100 percent compounded annually, cash (i.e., gold) is loaned out with no interest; rather, it is an investment from which the lender gets a percentage of the profits it earns. Indeed, it is just possible that Loarca gives a hint of a new form of usury which arose in direct response to his own encomendero presence: “Nowadays, some loafers who do not feel like looking around for their tribute to pay, ask to borrow it and return a bit more.”

THE SECOND ORDER

The timawa are personal vassals of a datu to whom they bind themselves as seafaring warriors; they pay no tribute, render no agricultural labor, and have a portion of datu blood in their veins.· Thus the Boxer manuscript calls them “knights and hidalgos,” Loarca, “free men, neither chiefs nor slaves,” and Alcina, “the third rank of nobility” (nobleza). Although a first-generation timawa is literally the half-slave of some datu sire, once he achieves ginoo status through liberation, he is free to move to any settlement whose lord is willing to enter into feudal relations with him. Such contracts call for the timawa to outfit himself for war at his own expense, row and fight his datu’s warship, attend all his feasts, and act as his wine-taster; and for the datu, to defend and avenge the timawa wherever he may have need, risking his person, family, and fortune to do so, even to the extent of taking action against his own kin. The timawa are his comrades-at-arms in his forays and share the same risks under fire, but they are clearly his subordinates: they have no right to booty beyond what he gives them, and they are chided for battle damage to his vessel but not held liable. But as his comrades-at-arms, they share in the public accolade of a society which esteems military prowess so highly that women are courted with lyrics like, “You plunder and capture with your eyes; with a mere glance, you lay hold on more than mangayaw-raiders do with their fleets.”

The timawas’ relations with their datus are highly personal. When they attend his feasts and act as wine-tasters, they are there as his retinue and familiars – “out front in the main sala,” as the creation myth puts it. If they are not their datus’ actual relatives, they behave like relatives: they are sent as emissaries when he opens marriage negotiations for his son, and they enjoy the same legal rights in prosecuting adultery. They are men of consequence in the community and may be appointed stewards over a datu’s interests. At the time of his death, the most prominent among them acts as major domo to enforce his funeral taboos, and three of their most renowned warriors accompany his grieving women folk on a ritual voyage during which they row in time to dirges which boast of their personal conquests and feats of bravery. But they are not men of substance. Although they may lend and borrow money or even make business partnerships, their children, like everybody else in the community, inherit only at their datu’s pleasure. As Loarca says in speaking of weddings, “the timawas do not perform these ceremonies because they have no estate (hacienda).”

The Timawa’s Distinct Role. Since both datu and timawa are what would be called non-productive members of society in Marxist terms, they form a single class in the economic sense, just as Legazpi thought they did. But in the Visayan body politic, the timawa serve a separate and distinct function: they are the means by which the datus consolidate their authority and expand their power. By limiting their own birthrate, monopolizing advantageous marriages, and controlling inheritance, they preserve their authority; and by producing a brood of warrior dependents tied to them by both moral and economic bonds, they provide themselves with a military support whose loyalty can be expected, thus suppressing competition to a considerable extent. Such social specialization would serve a trade-raiding society well, and may have been doing so for centuries before the Spaniards arrived. Medieval Chinese merchantmen avoided Visayan waters because of the notoriety of their slavers, and Chinese records indicate that Visayan raids were not unknown on the coasts of China itself. But the timawa role was destined not to survive serious modification of this economy. Datus with control of cotton-spinning underlings, or irrigated rice lands to apportion their followers, would have less need for such Viking services. And whatever needs remained would quickly be disoriented, deflected, and destroyed by occupation by a superior military power. The history of the word timawa suggests that just such changes took place in the Philippines in the sixteenth century.

When the Spaniards first met the timawas in the Visayas, they were the hidalgo-like warriors Loarca describes. But in fertile wet rice lands around Laguna de Bay and the Candaba swamps, they were found to be “plebeians” and “common people,” farming rather than fighting. As Plasencia says of them in Pampanga, “every chief who holds a barangay orders the people to plant, and has them come together for sowing and harvesting.” Their former military functions were now being performed by another order with the elegant name of Maharlika (“great, noble”) who were probably the genetic overflow of the aristocracy which occupied, or arose in, the Laguna lake district earlier in the century. By 1580, however, many of these “noblemen” found themselves reduced to leasing land from their datus. By the end of the century, any claim to Filipino royalty, nobility, or hidalguia had disappeared into a homogenized principalia, and the word timawa had become the standard term to distinguish all other Filipinos from slaves. Thus did the King himself use it in his instructions to Governor Gomez Perez Dasmarifias in 1589, as well as the Archbishop of Manila in promulgating a graduated scale of stole fees in 1626. And in Panay, meanwhile, regardless of whatever changes had already affected the timawa calling, Loarca was helping to make it completely dysfunctional by the exercise of foreign military power. As former warriors had to seek their living by other means, he found it necessary to describe their order not simply as timawa but as “true” timawa or “recognized” timawa, as if there were counterfeit versions around. If there were, they would have been victims of the inflation which led to the term’s final debasement in the modern Visayan word, which means “poor, destitute.”

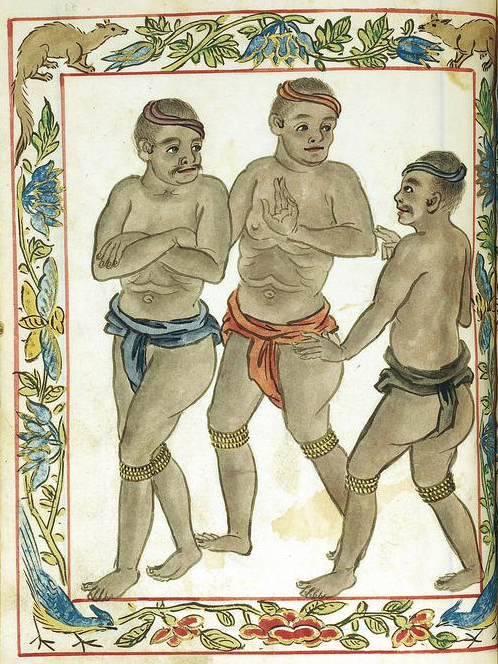

THE THIRD ORDER

Oripun are commoners in the technical sense of the word, that is, they cannot marry people of royal blood (datus) and are under obligation to serve and support the aristocracy of the First Order and the privileged retainers of the Second. They are under this obligation not because they are in debt, but because it is the normal order of society for them to be so; it is the way mankind was created. Their usual service is agricultural labor, and a distinctive characteristic of the upper two orders of society is that datus and timawas do not perform agricultural labor. Within this limitation, however, members of the Third Order vary in economic status and social standing, from men of consequence (who may actually win datu status through repute in battle), to chattel slaves born into their condition in their master’s house generation after generation. And at the very bottom of the social scale, the oripun technically include – if for no other reason than that there is no place else to assign them – those non-persons destined to join some deceased warlord in the grave, along with Chinese porcelains and gold ornaments.

The class of oripun is common to all the Visayan accounts, but the particular subclasses which reflect the socioeconomic variations within it differ considerably. The differences are not merely in terminology, as would be expected from Samar to Mindanao, but in actual specifications. In the most favored condition, for example, are Loarca’s tumataban and tumaranpok, the Boxer manuscript’s horo-hanes, and Alcina’s gintobo or mamahay, all of whom can commute their agricultural duties into other forms of service such as rowing or fighting or actual payments in kind. Loarca’s ayuey (“the most enslaved of all”) only serve in their master’s house three days out of four, and in the Boxer manuscript (which spells it hayoheyes) they move into their own house upon marriage and become tuheyes who do not even continue further service if they produce enough offspring. Plasencia’s “whole slaves,” however, for example the four-generation lubus nga oripun, hand over the whole fruits of their labor. This is a stricture which may be the result of social breakdown under colonial domination, since a characteristic of Philippine slavery, otherwise universally reported, is the theoretical possibility of manumission through self-improvement. These variations no doubt illustrate different economic conditions, crops, markets, and demands for labor, as well as individual datus’ responses to them. They also illustrate a social mobility which ultimately embraces all three social orders.

Condition of Higher Subclasses. Oripun are born into the Third Order just as datus and timawa are born into the other two. But their position within the order depends upon inherited or acquired debt, commuted criminal sentences, or victimization by the more powerful – in which latter case they are said to be lopot, “marked, creased,” or, as Alcina puts it, “unjustly enslaved.” Those in serious need may mortgage themselves to some datu for a loan, becoming kabalangay (“boat-mates”?), or may attach themselves to a kinsman as bondsman, but debts can also be underwritten by anybody able and willing to do so. The tumata ban, for example, whom Loarca calls “the most respected” commoners, can be bonded for six pesos, their creditor then enjoying five days of their labor per month. The status of tumaranpok, on the other hand, is reckoned at twelve pesos, for which four days’ labor out of seven is rendered. Both of these oripun occupy their own houses and maintain their own families, but their wives are also obligated to perform services if they already have children, namely, spinning and weaving cotton which their master supplies in the boll, one skein a month in the case of the tumataban, and a half month’s labor in the case of the tumaranpok. Either can com mute these obligations to payment in palay: fifteen cavans a year for the former, thirty for the latter. Thus a tumataban’s release from field labor is calculated at five gantas a day and a tumaran pok’s at three and a half. So, too, the creditor who underwrites a ₱12 tumaranpok debt receives 208 days of labor a year, but one who invests in a ₱6 tumataban, only 72. Since Loarca states that rice is produced in the hills in exchange for coastal products, such commutation enables an uplander to discharge his obligations without coming down to till his master’s fields. A coast dweller, on the other hand, has to be a man of considerable means to assume such a tribute-paying pechero role.

Another oripun condition is that of horo-han (probably uluhan, “at the head”). These perform lower-echelon military service in lieu of field labor, acting as mangayaw oarsmen or magahat (“foot soldiers”) and their children take their place upon their death (but have no obligation prior to it). They are part of the public entertained and feasted during a datu’s ceremonial functions, where their presence moved the author of the Boxer manuscript to comment with tourist-like wonder, “they are taken into their houses when they give some feast or drunken revel to be received just like guests.” The oripun called gintobo, mamahay, or johai also participate in raids, though they receive a smaller portion of the booty than timawas, and if they distinguish themselves regularly enough by bravery in action, they may attract a following of their own and actually become datus. They are also obliged to come at their datus’ summons for such communal work as house-building, but do not perform field labor; instead they pay reconocimiento (a recognition-of-vassalage fee) in rice, textiles, or other products. But, like the timawa above them and indentured bondsmen and slaves below, they cannot bequeath their property to their heirs: their datu shares it with them at his own pleasure. This arbitrary inheritance tax enables a ruling datu to reward and ingratiate his favorites, and leave others under threat of the sort of economic reversal which sets downward social mobility in motion. A ₱12 debt can plunge a man into the depths of ayuey household slavery, with the high probability of transmitting that status to his offspring since any children born during his bondage will become the property of his master.

The Ayuey Condition. These ayuey are at the bottom of the oripun social scale. They are, literally, domestics who live in their master’s house and receive their food and clothing from him, and who are real chattel. As Loarca says, “those whom the natives have sold to the Spaniards are ayuey for the most part.” They either have no property of their own or only what they can accumulate by working for themselves one day out of four. They are generally field hands with the same manumission price as the tumaranpok, namely, 12, and their wives work as domestic servants in their master’s house. They are usually single, however, but are given a separate house when they marry and become tuhey, working only two days out of five. Their wives, however, continue to serve until they have children; then, if they have many, they and their husbands may be absolved of all further ayuey servitude. Their children, needless to say, do not inherit.

First-generation ayuey are debtors, purchases, captives, or poverty-stricken volunteers seeking security. Those who are enslaved in lieu of payment of fines are called sirot, which means “fine,” and those seized for debts, or imputed debts, are lupig, “inferior, out-classed.” Creditors are responsible for their debtors’ obligations; so another route by which commoners are reduced to ayuey status is for their creditors to cover some fine they have incurred. Purchases may be outright, for example, adults or children in abject penury, or by buying off somebody’s debt, in which case the debtor becomes gintubus, “redeemed.” Actual captives are bihag, whether slave or not at the time of capture, and are sharply to be distinguished from all other ayuey because of their liability to serve as offerings in some human sacrifice. (Loarca notes approvingly, “they always see that this slave is an alien and not a native, for they really are not cruel at all.”) It is not impossible that Spanish disruption of traditional slaving patterns produced an increase in domestic oppression on the part of those datus who were called principales. At least Alcina comments, “they oppressed the poor and helpless and those who did not resist, even to the point of making them and their children slaves, [but] those who showed them their fangs and claws and resisted were let go with as much as they wished to take because they were afraid of them.” But, in any event and whatever their origin, first-generation ayuey all have one thing in common: they are the parents of the second generation “true” slaves.

The “true” slaves, as distinguished from those commoners of varying degrees of servitude who are slaves in name only (nomine tenus, as Alcina says) are those born in their master’s house. The children of purchased or hereditary slaves are called haishai. If both their parents are houseborn slaves like themselves, or purchased, they are ginlubus (from lubus, “all one color, unvariegated”), and if they are the fourth generation of their kind, lubus nga oripun. But if only one of their parents is an ayuey of their status, they are “half slaves” (bulan or pikas) and if three of their grandparents were non-slave commoners, they are “one-quarter slaves” (tilor or sagipat). “Whole slaves” may also be known as bug-us (“given totally”) or tuman (“utmost, extreme”). But some of them are cherished and raised like their master’s own children, often being permitted to reside in their own houses and usually being set free on their master’s death; these are the silin or gino gatan. Thus there is no given word for “slave,” but only a graduated series of terms running from the totally chattel bihag to the horo-han commoner (“at the head”) in the upper level of the oripun order. And the initial step up this social ladder is the normal expectation of the houseborn ayuey at the bottom, for when his master marries him off to another houseborn ayuey, he is set up in his house where he and his wife serve both masters. When his children are born, they become slaves to both masters too, but as soon as they grow up, he himself assumes tumaranpok status. Thus as Visayan house slaves move upward into the dignity of vassalage, they leave enough of their offspring behind to supply their masters’ needs.

CONCLUSION

The sixteenth century Spanish accounts say that Filipino society is divided into three classes, to which they assign the European feudal concepts of rulers, military supporters, and everybody else. This having been said, they proceed to give information which indicates that this three-class analysis is inadequate for an understanding of the society being described. On the one hand, in economic terms, the three classes appear to be only two. In Loarca’s Visayas, for example, the upper two classes live off food and export products produced by the third class, while in the Tagalog areas reported by Morga and Plasencia, the lower two classes work the fields of the upper. On the other hand, in social terms, the indigenous class designations are not readily reduced to three, and, worse yet, seem to shade off into one another confusingly. This confusion probably arises not so much from an inadequacy in the Spanish descriptions as from the basic fallacy of originally expecting to find three – or any other number – of static pan-Philippine social classes. What might more logically be expected would be the description of a society, or societies, observed in the process of change, that is, of class structures caught in the midst of ongoing development and decay, so to speak. Such an expectation can be readily fulfilled by a reconsideration of the accounts.

VISAYAN CULTURE

Of the two cultures described, Visayan and Tagalog, the former appears to be the more basic and stable – not stable in the sense of unchanging, but in the sense of being flexible enough to absorb such changes as confront it. This flexibility is provided at both the top and bottom of the social scale. At the one end, a chief can retain and restrain competing peers, relatives, and offspring if he has the personality and economic means for it; but if not,they can migrate to other communities that can use their services, or found new ones of their own. At the other end, the owners of chattel slaves can demand their and their children’s services if they have need of them, but are not obligated to do so. The political units of this society are small – less than 1,000 persons at most – and are potentially hostile to one another unless related by blood, intermarriage, trading partnerships, or subjugation through conquest. Weaponry is too unsophisticated to be monopolized by individuals, so political power is exercised through client-patron relationships. The economy is based on products from swiddens, forests, and the sea, and their redistribution a pattern of trade-raids which make public protection necessary. Chiefs fulfill this function by means of specialized warships designed for speed, maneuverability, and operation in shallow, reef-filled waters, but with limited cargo capacity. These are the conditions to which Visayan social structure is fitted, as those of Mindanao and Luzon probably were in their day, too.

The chief of a Visayan community is called a datu, and the social class to which he belongs is called by the same term. A lesser aristocracy descended from former or subordinate datus is called tumao and provides the datu’s officers, retinue, and bodyguard. Descendants of a datu’s illegitimate offspring are called timawa and constitute a warrior class whose members may attach themselves to a datu of their choice. These three social classes form an economic upper class supported by the labor of a lower class called oripun who are born, impressed, or sold into their class. A variety of statuses or subclasses have been generated among them by a society’s particular needs for labor or crops, and differences of personal debt. Most members of this class live at such a low subsistence level that debt is a normal condition of their lives: it arises from outright loans for sustenance or from inability to pay fines, and its degree determines individual oripun rank. Among these subclasses are the following;

Ayu-ey: a domestic slave or bondsman whose offspring are the property of his master.

Bihag: a captive.

Ginlubus: the child of two domestic slaves, born in their master’s house.

Ginogatan: a cherished household slave favored with separate quarters and usually liberated upon his master’s death.

Gintobo: an oripun who performs military service and also pays a vassalage fee in kind.

Gintubus: any oripun whose debt has been underwritten by another man.

Haishai: the child of a purchased or hereditary slave.

Horo-han: a high-status servitude of military service in lieu of field labor, but passed on to the next generation.

Lupig: any oripun seized for debt.

Sirot: any oripun whose status results from an unpaid fine.

Tu-ey: a married ayu-ey set up in housekeeping by his master; he normally becomes a tumaranpok when his children are old enough to re place him.

Tumaranpok and tumataban: two grades of servitude requiring specified kinds and periods of labor from both man and wife; the first is reckoned at twice the second in terms of debt or tribute if labor is commuted to payment in kind.

ALSO READ: TAGALOGS Class Structure in the Sixteenth Century Philippines

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.