The Visayan Islands are, in Philippine folk belief, the home of witches. Whatever might have led to this “distinction,” investigation showed that the belief in witches and witchcraft is common to all segments of the population in the barrios as well as in the towns of Leyte and Samar. Even many intellectuals have not given up this belief, and the fear of witches and witchcraft is common.

The data in this study collected from different barrios and towns in Leyte and Samar showed a definite pattern of belief. Through field trips, interviews, and reports this general pattern has been established. Interesting stories had to be put aside to shorten the report; only the characteristic elements have been listed. No attempt is made to solve inconsistencies resulting from different reports and interviews, because it is the privilege of these folk beliefs to be inconsistent. Nevertheless the variations are minor; far more impressive is the unity, even in details, about witches and witchcraft in the area concerned. This uniformity of belief even among the remotest barrios on the two islands suggests an origin from an earlier culture. Comparative studies from Indonesia and Indo-China might shed more light on this matter.

The lack of competent literature in the province, travel restrictions imposed by the author’s occupation, and lack of funds made comparison with the other islands of the Visayas impossible. Whatever meager information is available concerning the other Visayan islands: Negros, Cebu, Bohol, Panay, nevertheless confirms the same pattern of belief and makes it therefore probable that this study is representative for the Visayas in general.

CONCEPTS

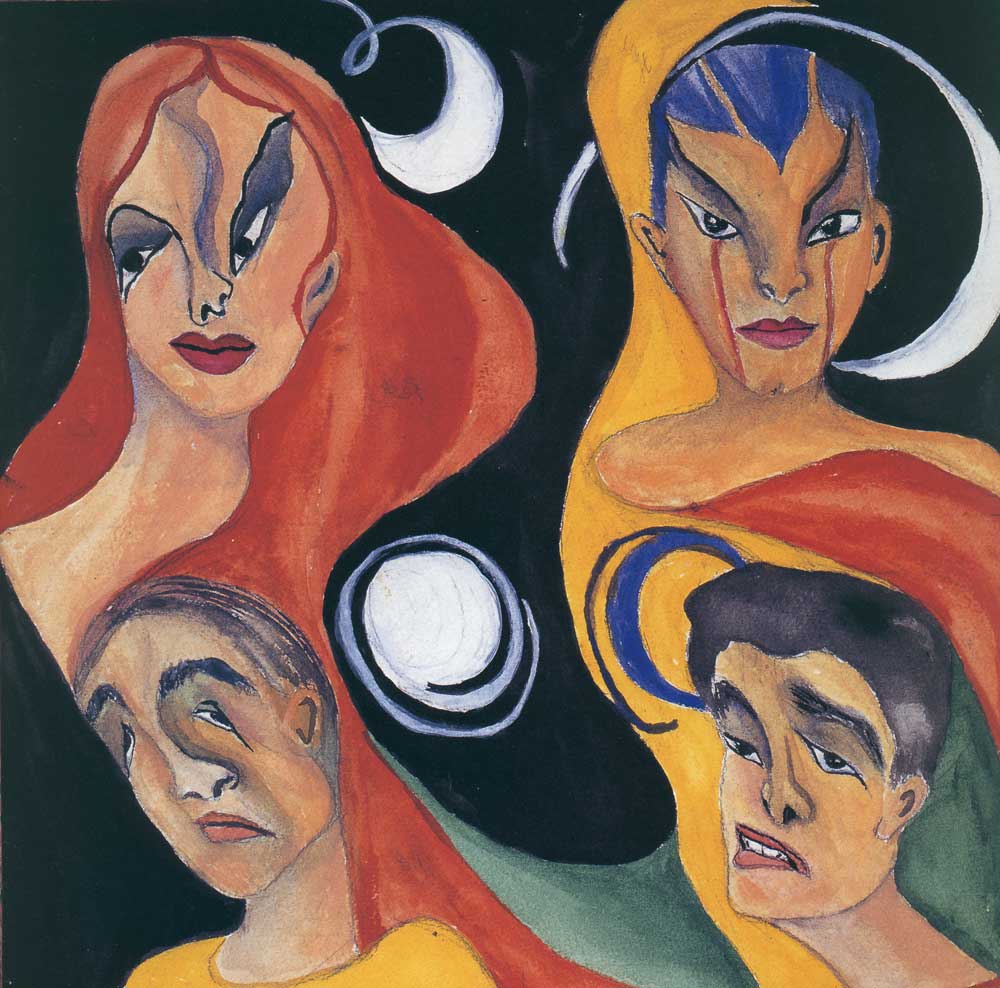

In the Waray-waray dialect – spoken in Samar and Eastern Leyte- the witch is called aswang and can be either male or female. In Hilongos (Western Leyte) where Cebuano is spoken, the term aswang refers not only to the witch proper but also to a whole group of ghostlike beings.

1. Agtas, who are short and small beings with enormous eyes, are said to live in mangroves and other swampy places. They are always seen laughing and sometimes smoking a little pipe and leaning on the trunks of small trees growing in such places.

2. Phantasmas, who are big and tall “madres” or ”padres” with white clothing, appear usually just when it begins to get dark and on midnights when the moon is bright. They do not live in a particular place and are believed to appear and vanish into thin air. They are always seen walking in streets and small trails leading to interior barrios when these are deserted. They wear a wistful look and a far-away glance. When someone meets a phantasma it is believed that the phantasma will do no harm if the person will only stay at the roadside and not block the way. He must not meet the phantasma or pass it by. Most often a “padre” phantasma appears to a girl and a “madre” phantasma to a boy.

3. Ungos and bawos are big and muscular men dressed only with a loin cloth. Children “see” them smoking the biggest pipes and sitting on the branches of big trees called nunok which are their permanent homes. In the daytime the ungos and bawos are not seen but the people sense the presence of one or a group of them because they play jokes and, when disturbed, get angry. When they play jokes they either give one a big latik (flick) on the head with their unseen forefinger or steal his firewood, basket, or clothing. When they get angry, they are so powerful that they cause serious sickness which even the quack doctor cannot cure. Only very few adults who know a certain oracion may go near or under the big trees which the ungos and bawos inhabit, or attempt to cut their branches.

4. Sigbens are goat-like animals with big, wide and prominent ears but no horns. They appear and are seen only in the evening; they are invisible during the day. In the evening they stay under the house of a dying person. They come back for nine consecutive nights, until the accustomed novena for the dead is over. Their bodies produce a very pungent and nauseating odor and their big ears clap like two pairs of hands at the sides of their heads.

5. Ugkoys live in fresh water and are usually seen in rivers during floods. Their favorite hobby is dragging down their victims by the feet to the bottom .

6. Santelmos are the souls of those who drowned in shipwrecks and storms. They live in the sea. They seldom appear in shallow water or on river banks. They like the deep sea better because they can easily get their victim when he is alone. The fishermen who fish at night and are never seen again are said to be victims of the Santelmos. The Santelmos rise to the surface of the sea during rainy days. Even deep down at the bottom of the sea they can be seen, because their bodies are said to be luminous.

7. Abats and awoks are the most dangerous beings who “really” strike and do harm to men. They have only the upper parts of their bodies. They have big, red, bulging and hungry eyes, disheveled hair, and long, bony, clawed fingers. They can fly with only their heads and hands. Their favorite food is small children. They are active only at night and can travel long distances. The abats of a town can visit neighboring towns. They fly over nipa houses in which live pregnant women.

The abats and awoks have qualities which in Samar and Eastern Leyte are attributed to the witch. The difference between witches and the other ghost-like beings already mentioned consists in the fact that the witch belongs to the human race and is only possessed by an evil spirit, whereas the ghost-like beings do not belong to the human race, although some of their habits are like those or humans.

In Samar-Leyte folk belief, witches are human beings possessed by an evil spirit and endowed with magic powers. The Leyteños and Samareños group witches into two kinds : ( 1) the malupad (fying witch) and (2) the malakat (walking witch).

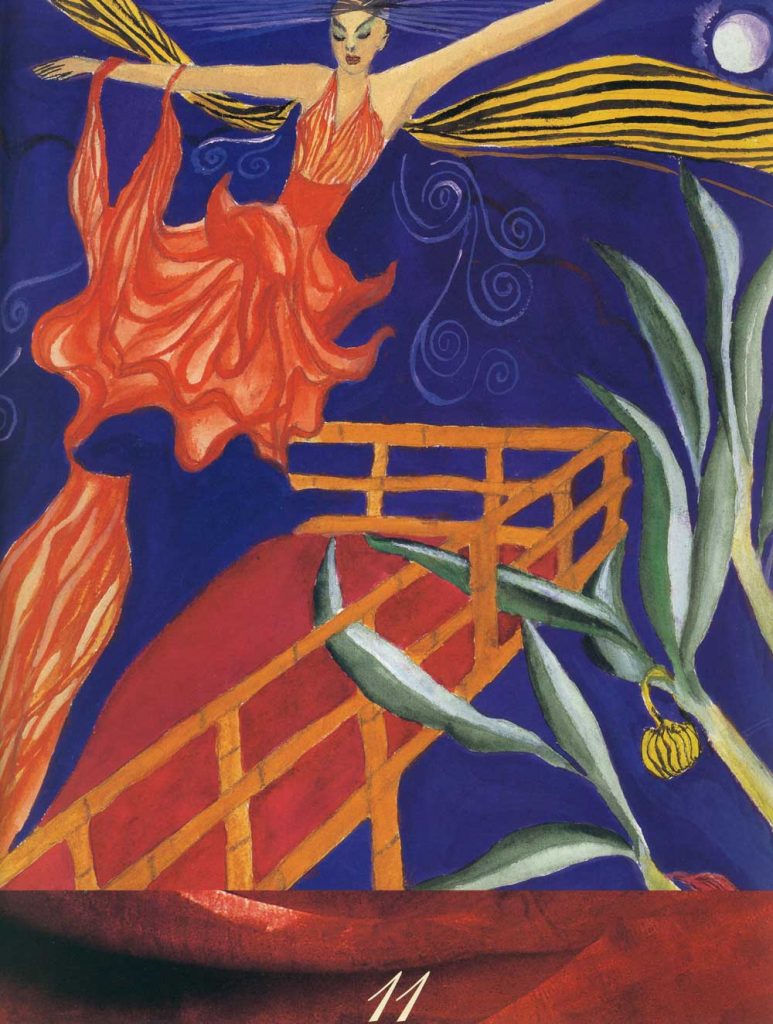

The flying witch, also popularly called “night pilot,” generally flies at midnight. Her presence is announced by the cry of “wakwak” which comes from a bird that accompanies her. Another name for the witch is therefore wak-wak. The bird sits on the roof of a house where someone is sick or a woman is about to give birth. The witch goes under the house and brings harm to the sick person by sucking his blood and to the new born baby by eating its liver.

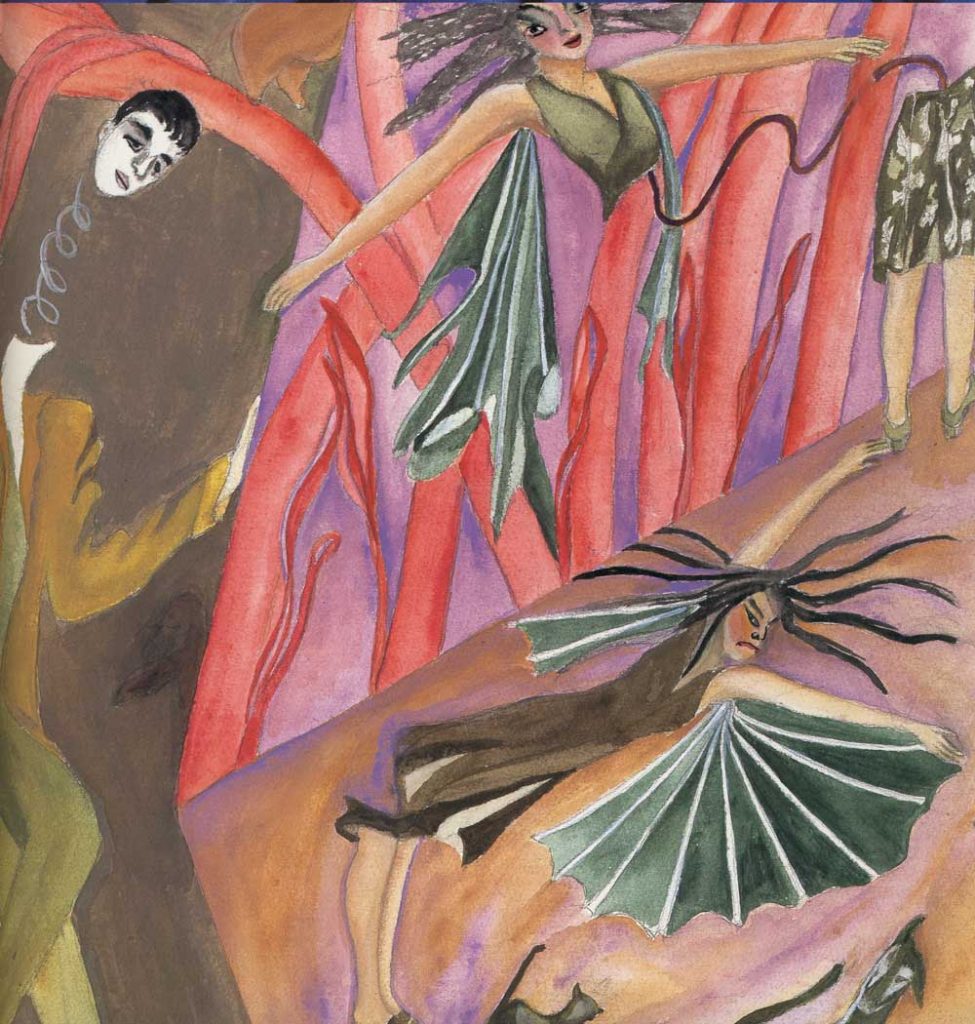

The walking witch goes out at night or even at daytime, and hides in secluded place? As soon as she decides to attack a person she becomes a horrible and frightful sight. Her long hair spreads over her face. Her eyes turn fiery and her saliva flows out from her mouth like long strings. Her nails grow long and sharp. As the fight begins her hair crawls into the person’s nose, ears, mouth and eyes depriving him of breath, voice, and sight. She grips her victim firmly on the arms and legs. With her sharp claws she digs into her victim’s skin until he bleeds. If she has a weapon with her, she avoids the struggle and might kill her victim. Thereafter the witch feasts on his blood and flesh.

ORIGIN OF WITCHES

How the first witches came into being has been forgotten by the people; at least the writer could not establish a common pattern for the witch’s origin. The oldest informant only said, “Since time immemorial the witches have been on earth.”

It seems that the “cave spirits,” also called “spirits of the mountains,” made the first witches. At least this is the belief in Abuyog, Leyte. It is said that during Lent the caves – the homes of the spirits – are opened and only those who know the magic words (oracion) can enter them. In the caves are bottles with plants. If someone finds a bottle i n which a plant is growing naturally, that is, with roots down and leaves up, he will become a good quack doctor; but i”f he finds a bottle with an inverted plant he will automatically become a witch or aswang.

Folk belief is more concerned with how witches come into being today. Two explanations seem to prevail, namely: by inheritance and by physical contact with a witch.

At the deathbed of a bewitched family member one can become a witch through inheritance. Witchcraft in the family is transmitted to the member best fitted to inherit the power. Inheritance is therefore not through birth but by transmission. If, for example, the father was a witch and dies, the witchcraft is given to the mother; after her death it is given to the eldest son or daughter. Thus, not all members of a bewitched family are witches.

One way to become a witch by physical contact is through food and drink offered by a witch. The witch is in human form when she does this; and she has previously placed a germ in the food or drink she offers. In the stomach of the victim the germ develops into a small monster the size or a bird. As soon as the monster has fully developed, the newly bewitched person becomes strongly imaginative and feels an urge to suck fresh blood from warmblooded animals including human beings. When hungry, she sees things not as a normal person sees him. In the egg, for example, she sees the developed chicken; in a pregnant woman she sees the little child. At this moment she develops a strong urge to feast on these living things. To satisfy her craving she flies at night to the house of a pregnant woman or a sick person to suck her blood; or she transforms herself in to an animal for the same purpose.

Witchcraft is also transmitted if a witch touches a person with that intention. To counteract the spell, the victim has only one remedy, namely, to touch the witch quickly in return.

A witch can also transmit her power with her breath. She blows on the victim’s alimpoporo (crown of the head).

To be present at the agony of a witch is another occasion to become one. Shortly before the last breath of the dying witch, the monster in her stomach leaves her body to look for a new habitat. It enters another person who will for “certain” become a witch if the animal finds him satisfactory. If not, that person will become paler and paler and finally die.

A witch develops in stages. First stage: The germ incubates in the newly bewitched person’s stomach. At this time she often has stomachaches, a condition described as sinusuruksurok. She feels

uneasy during the day, but is very active at night. In this stage the sickness can be easily “cured” by a tambalan.

Second stage: After suffering for about a month from stomach pain, the bewitched person develops an appetite for raw chicken. As soon as she sees a chicken, her saliva starts flowing.

Third stage: In the third stage the witch teaches her victim how to fly and how to go to sick persons or pregnant women especially at the time of delivery. At this time the bewitched person can be seen at night in the backyard or under the house of the sick person since he or she is not yet an expert in flying and escaping. This is the time to detect a newly bewitched person. At this period the “disease” is very hard to cure.

Fourth stage: In the fourth stage the person becomes an expert wak-wak and can no longer be cured. If she submits herself to a tambalan for a cure, she will die.

OUTWARD APPEARANCE

In spite of the many variations in details arising from fertile imaginations and fondness for story telling, it is remarkable how a standardized pattern in the description of a witch is preserved. There is general agreement. that the witch in ordinary life is a rather acceptable and normal person. She changes at nighttime, or sometimes in the daytime, when she comes under the magic spell, i.e., when she gets hungry and has the craving for blood and human flesh. Then her eyes glow reddish, they become sharp and penetrating, enabling her to see through a pregnant mother to the child in the womb. Her teeth become sharp and her fingernails long and pointed like swords, fit tools for feasting on the blood and flesh of the sick, on newborn babies, and on corpses newly buried in the cemetery.

Her hair is brittle, straight, and spreading, giving the witch a wild and furious look. Saliva drips from her mouth at the time she is prowling for prey. Her body is thin and slippery, making it possible for her to fly or crawl through the smallest opening. The witch in this state ( napoó) is a devilish sight.

HABITS OF THE WITCH

According to the people in Giporlos (Samar), the witch has a big jar. Every night she crawls head first into the jar and stays there in a vertical position. In this position, the witch hears the moaning of sick persons within a wide radius. As soon as she determines her victim, her wings grow on the instant and she flies to her destination. There she goes under the house and is transformed into the animal incubated in her which may be a dog, a cat, a pig, or the like. After she has sucked the blood of the sick person and eaten part of his internal organs such as his liver and intestines, she goes home and feeds her pet animals.

The flying habits of the witch are similarly described by informants from Leyte and Samar. The witch ordinarily flies at midnight. Before her flight she applies magic oil under her armpits; this make her wings grow instantly. The witch detaches the upper part of her body (head, shoulders, and hands) from. the lower part (waist below). With only the upper part of her body, she flies away, leaving the lower part in a certain position. Should someone alter this position while the ·witch is away, the witch would not be able to unite the parts anymore and she would die.

Their carnivorous habit is the outstanding characteristic of witches. They prefer the blood of sick persons and pregnant women. Before they start sucking, they dance the “mambo-tambo,” laughing while they perform it.

The flesh of infants, especially the liver, is a delicacy for them; therefore witches like to be midwives. They steal newborn babies and substitute banana trunks for the stolen babies.

Witches often visit cemeteries to watch for new burials in order to feast later on the bodies. Their long- fingernails and sharp teeth are especially fit for this work.

They live in houses without roofs and with floors that are not all nailed so they can go out readily. They do not molest their immediate neighbors, but exercise their evil powers far away to keep their secret from their neighbors.

THE POWERS OF THE WITCH

Witches have many powers, the most common and important of which is the power of transformation. In the pursuit of prey a witch can take the form of any animal she likes, preferably that of the one incubated in her at the time she was bewitched. The most common form assumed is that of a dog, cat, or pig. This transformation is called salipdanan, a taking cover, or a camouflage.

If a witch is wounded while in her animal form, the wounds inflicted on the animal will appear also in her human form. Witches heal their wounds with their sticky saliva.

The power to fly, to harm other persons, and to transmit their power or bewitch other persons have been mentioned earlier in this report.

In some places, the power of barang is ascribed to witches. Barang is the power to inflict harm on persons. Because barang results in evil effects, this power has been attributed to witches. It is said that this power was originally transmitted by cave or mountain spirits and fairies. Nowadays it can also be acquired through the process of tahas. Only persons who are brave and have strong convictions can acquire the barang power. In order to become a barangan (one who has the barang power) one must show bravery by going at nighttime to the cemetery to talk to the

dead or by going to a church when the clock strikes 12 midnight. It is said that if someone attempts the tahas and does not continue out of lack of bravery, he will go crazy; therefore very few are believed able to acquire the power of barang.

A good effect of the power of barang is that one possessing it can cure a sickness caused by fairies and evil spirits. The barangan in this way acts like a tambalan.

Among the evil effects attributed by folk belief to barang is the ability of the barangan to kill anyone by mere words, the so called oracion. The barangan may also cause facial deformation; the person afflicted loses either his nose or another part of his face.

Persons who wish to do harm to their enemies quite often secure the help of a barangan who with his power can cause the desired harm. It is also folk belief that a full-fledged barangan has a whole supply of “invisible destroyers,” in the form of germs and insects, which can be sent to the intended victims. A protection against the barang is the wearing of gold or of a bullet. This makes a person invulnerable. As mentioned before, the barangan is not necessarily a witch, but witches have the barang power.

Other powers of the witch are connected with her power of transformation : she can make her weight so light that she can easily sit on the twig of a tree; she can go through the smallest holes. Upon applying on her body the magic oil: which she jealously keeps, she becomes very strong, slippery, fast, and almost invisible. She has also a keen sense of smell, with which she can discern people from afar; through it, she finds those who are sick. A witch can smell the sick and the dead however far. The sick and the dead have a sweet smell to the witch. Her eyesight is extremely keen, especially at night.

PROTECTION AGAINST WITCHCRAFT

A witch is highly feared throughout Leyte and Samar. To counteract her magic power, one may adopt natural precautions or use magic antidotes or charms.

If a person is sick or a woman is about to give birth, the house is well guarded against witches. Sharp bolos are inserted between the bamboos of the floor, so that the witch will cut her back or wings if she crawls under the house. Sometimes sharp-pointed bamboo sticks are used for the same purpose. In other places a sogub (a spearlike weapon) is placed near the house to scare the witch.

Sick people should not stay in houses with big holes; their beds especially should not be near such holes, because it is through these holes that-witches with their slippery bodies gain entrance. Sick people are further admonished to abstain as much as possible from groaning and moaning, since these sounds attract the attention of the witches who are only too willing to pay them a visit at night.

Out of fear for witches, in general everyone is careful not to offend them; this people believed to be witches are treated with care and politeness. In Caribiran, Leyte, this politeness is carried so far that throwing anything out of the window at night , the people say “Tabi kamo dida; buta ako” (“Get away from there; I am blind”). It is believed that if one does not utter these words before throwing anything out, he will be punished by the witches.

Just as the witch uses oil to grow wings and fit herself for devilish tasks, in the same way folk belief has people using a sacred oil as a powerful protection and antidote (charm) against witchcraft. This oil is manufactured with great care and with solemn prayers. A slight error in the making of the oil will make it powerless. The oil is made from a selected coconut tree. The best fruit is picked after long observation and at a prescribed time. The best time for picking the coconut fruit is at twilight and in weather that suggests loneliness. The sea breeze should give a chilling touch and the moon should shine like a perfect marble ball.

After picking the coconut, the oil is prepared in the common way: the coconut is grated, the juice squeezed out, then boiled till oil is produced. The only difference is that only firewood from high mountains may be used. During the process of making oil, prayers are said with sincerity and solemnity. When after hours of processing the oil is made, the by-products are thrown into the depths of the ocean, so that the witch cannot find any traces of the person who made the sacred oil, for all fear the revenge of the witch. The effect of the oil is powerful. It makes a witch uneasy and unable to do harm to the holder of the oil.

The following story was told by an informant :

“Years ago my grandfather unknowingly married a witch. When he felt symptoms of witchcraft in himself, he made the sacred oil and gave it to his grandchildren that they might not be harmed by his bewitched wife. He knew that the best way to become a witch was through physical contact and by eating the food prepared by a witch. Since the grandchildren came often to the house and ate the food prepared by the bewitched grandmother, the oil was needed for their protection. The food used to transmit witchcraft is prepared from

a green leafy vegetable called gaway ( gabe).

“One time when they were getting ready for dinner, my father changed the seating arrangement, making sure that he would be sitting next to Grandfather ·who had lately shown more and more signs of being bewitched. My father pretended to be late and so could take the seat next to Grandpa. In his pocket he carried the sacred oil. Very soon Grandfather felt rather uneasy. Abruptly he left the table and went away and did not come back until the next day. For my father this was a sure sign that Grandfather was bewitched. It is common belief that one who has the sacred oil will not be harmed by the witches. ”

A simpler protection against witches is the use of table salt which is readily available, unlike holy oil which is known only to experts. It is said that witches are allergic to salt both in its liquid and solid forms. Salt ground with garlic and ginger is an even .more powerful compound dreaded by the witches because its pungent and sharp odor is said to be fatal to their olfactory sense. Burning rubber also drives witches away because its odor hurts their sense of smell.

A 105-year-old woman from Tigbao gave the following advice: “Use balangue or tikoko for firewood. Put anything that is scratchy (magirhang) in a bottle of oil, put the bottle in a cloth bag and hang the bag from your neck, carrying it along everywhere.”

HOW TO DETECT A WITCH

Before one can protect himself against the evildoings o£ a witch one must know to detect her presence. Folk belief has developed a number of devices. Every Leyteño and Samareño becomes alert upon hearing a bird cry “wak-wak” or “ki-kik” at night. He believes that a witch is hunting for human blood and flesh in the neighborhood. Unknown persons or animals found under a house after the cry is heard are suspected to be witches.

A witch may also be recognized thus: If you suspect someone to be a witch and you meet her in the daytime look her straight in the eyes. A witch will avoid your eyes because she cannot look straight into them. On certain days, namely, Fridays and the days of Lent, the image of an object in the eyeball of a witch is inverted. According to the old people this is a sure way of recognizing

a witch at daytime.

The holy oil mentioned above also plays a role in detecting a witch. A similar kind of oil is produced from a one-eyed coconut obtained on Holy Fridays. This oil, placed in a bottle, will start boiling in the presence of a witch; it is therefore a sure way to detect her.

When a member of a family is suspected by the others to be a witch, they turn her while asleep to another position. If the person is a witch, she will not wake up anymore, because the bad spirit will not be able to find its way back into her body.

A person fond of eating raw chicken is also highly suspected to be a witch.

HOW TO KILL A WITCH

No statistics are available on the number of people killed because they were suspected to be witches. But in distant barrios where strict enforcement of the law is not possible, witch killing is still going on;. 6 0 One informant said: “The asuangs in my home do not live long, because all the people are after their necks.” Another said: “In our place we have still one witch, the rest having been killed or having moved to far-away places where they are not known.”

Certain “sure” methods of killing a witch are known in folk belief. An informant from Carigara said: “To kill a witch is quite hard, for the older the witch the stronger she becomes. As soon as you have seriously wounded a witch, plant your dagger in the ground, and the witch will not survive. If you don’t do that, the witch will apply her oil to the wounds as soon as you have left her, and she will be healed.”

Another informant from Carigara said that the best way to kill a witch is not a gun, but with a sharp pointed bamboo. The witch should be stabbed in the back with the bamboo and her body slashed to pieces. One should also recite certain prayers (oracion), because the prayers render the witch paralyzed and helpless.

If the witch appears in the form of an animal, the people of La Paz, Leyte, say that one should strike the animal at the tail since that is where the witch is holding it. If the tall is hit, the the prayers render the witch paralyzed and helpless.

The people of Balangiga, Samar, say that to stab and to slash a witch who appears in the form of an animal is useless, unless one cuts the animal into two and brings each piece to opposite parts of the river. In this way the witch cannot unite the parts anymore and will die the following morning. If the parts are not separated, the witch applies some leaves to the wounds, says some words, and

is healed.

THE SOCIAL STANDING OF A WITCH

The social life and reputation of a witch in a community is complicated. Besides being feared, the witch is the most despised and detested person in the community, in spite of some good traits which – the people believe – are only a cover-up for her inhuman behavior.

In Alangalang, Leyte, the people say, “Witches are respected because we fear them as human beings they are also respected because they are quiet and reserved . They do not go to social gatherings unless they are invited. They are very friendly if you are good to them. They are the most hospitable people. They indulge little in alcoholic drinks. You cannot hear them quarrel with other people unless, of course, they are provoked. They are diligent and industrious and attend to their work seriously. They are somewhat individualistic because they must rely upon themselves; they prefer not to seek advice from other people. They seldom complain when they are given work to do. But if they refuse to do something, one should be understanding and not insist on it.

In Dagami (Leyte) the good traits of witches are also explained as a cover-up. An informant said: “During the day the witches are like us. They participate in social activities; they are devout Catholics and they attend Mass everyday and receive Holy Communion. But we know that they are only pretending so that they will not be suspected. ”

The life of a suspected witch and her family is made difficult by the constant suspicion of the people. The “witch” is shunned and sometimes publicly embarrassed. Food and delicacies sent from her kitchen out of hospitality are thrown away or fed to the dogs. Endless gossip circulates about her horrible and inhuman ways such as feasting on a dead man’s body which someone will claim to have seen her doing the night before. The family members are the targets of many sarcastic and cutting remarks. The pretty daughters stay unmarried because young gentlemen are afraid to marry them.

There are a few persons who would like to become witches for the simple reason that “witches can enjoy everything precious in life. They can make many and long trips without being noticed and paying any amount, because they fly on their own power. They can see movies, carnivals, costly stage shows; they can get all the luxuries of life, for because of their power they can take jewelries from stores and money in any amount from a bank.” But these people are necessarily few because to be a witch is too risky. A big landowner in Biliran Island whose dog bit a tenant who died a few days later, began to be looked upon as a witch from that time. He had to build a high wall around his house and could not leave the house without protection. So it is still very dangerous to be called a witch in Leyte and Samar, because “the people are after their necks.”

CONCLUSION

The striking feature of this study is the standardized pattern of folk belief in witches and witchcraft that prevails in the Eastern Visayas. This pattern of belief is so similar even among the remotest barrios of Northeast Samar and Southwest Leyte, which have hardly any economic and social contact, that one can only assume that the belief has its roots in a common Southeast Asian culture.

Comparative studies should be made to determine these mutually related elements for Southeast Asia. Some beliefs are worldwide; for example, that witches change into animals; that if these animals are wounded, the same wounds appear in the body of the witch; that witches fly and eat human flesh. Other elements are of Christian origin, but one should be careful not to attribute to Christian origin, influence that might belong to an earlier culture assimilated by Christian culture. For example, is the use of “holy oil” a charm against witchcraft of Christian origin? The fact that it is prepared on Holy Friday points to a definitely Christian influence; but the use of oil for such occasions might have been in practice long before Christianity came. Again, is the use of salt as a charm against witches to be attributed to Christian practice in the exorcism during the baptismal ceremony, or is the use of salt for this purpose found in other areas of Southeast Asia where the native culture has not been modified by Christianity? Comparative studies on the subject may solve these and similar problems.

Folk belief in witches and witchcraft has its stronghold in the barrios from where it finds its way to the towns and cities through housemaids and visiting relatives who regale children with their horrible stories about ghosts and other beings which form the motifs of folk belief.

SOURCE:

Folk Practices and Beliefs in Leyte and Samar, Richard Arens, Divine Word University Publications, 1982

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.