Juan de Plasencia spent most of his missionary life in the Philippines, where he founded numerous towns in Luzon and authored several religious and linguistic books, most notably, the Doctrina Cristiana (Christian Doctrine), the first book ever printed in the Philippines. Among his various documentation is a list of “distinctions made among the priests of the devil”, from 1589 in the document called “Customs of the Tagalogs”. Some of the 12 “devils” listed are very similar to the creatures of Philippine mythology we know today – Manananggal, Aswang, and the Mangkukulam. Others are horribly misclassified – the Catolonan and Bayoguin stand out most prominently. Another problematic issue with the classifications are that some of these “devils” may have been considered malevolent deities by early Tagalogs. We have to remember that some of these mythical beings existed in the spirit realm and would, on occasion, appear in human form. Even though they were considered harmful and the natives feared them, they were not considered “evil”. They just did what they were supposed to be doing.

Due to Plasencia’s Catholic mindset and the Spanish mission to cleanse the lands of “heathens”, early Filipino’s were trained, forced, or convinced to associate some of these beings with the devil. The Spanish were successful in eliminating the belief in deities and de-powering the spiritual leaders, but they were no match for superstitions regarding folkloric beings. Legazpi stated his mission soon after he arrived on the Islands.

” They easily believe what is told and presented forcibly to them. They hold some superstitions, such as the casting of lots before doing anything, and other wretched practices–all of which will be easily eradicated, if we have some priests who know their language, and will preach to them.” – Miguel Lopez de Legazpi (1565)

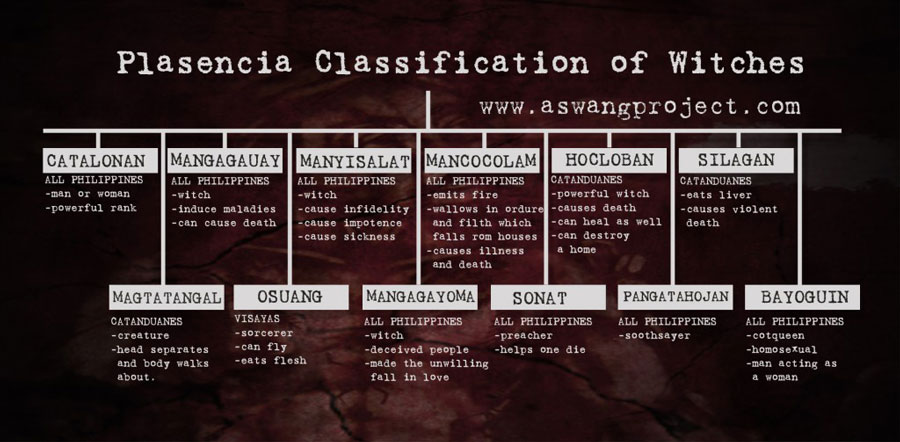

I’ve listed Juan de Plasencia’s classifications below, followed by what we know of the same beings today. We do need to be careful with our assumptions on this. In Outline of Philippine Mythology F. Landa Jocano takes some entries from Plasencia’s distinctions and categorizes them as deities. Comparative studies show that this could possibly be a case of over-correction.

Excerpt from: CUSTOMS OF THE TAGALOGS

by Juan de Plasencia, O.S.F.

From: The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898. Volume 7, 1588-1591

The distinctions made among the priests of the devil were as follows:

1. The first, called CATOLONAN, was either a man or a woman. This office was an honorable one among the natives, and was held ordinarily by people of rank, this rule being general in all the islands.

– We know today that the Catalonan were the Tagalog equivalent of the Visayan Babaylan and functioned as a healer, shaman, seer and a community leader.

– No distinction as a witch exists today.

2. The second they called MANGAGAUAY, or witches, who deceived by pretending to heal the sick. These priests even induced maladies by their charms, which in proportion to the strength and efficacy of the witchcraft, are capable of causing death. In this way, if they wished to kill at once they did so; or they could prolong life for a year by binding to the waist a live serpent, which was believed to be the devil, or at least his substance. This office was general throughout the land.

-In F Landa Jocano’s Outline of Philippine Mythology he wrote: “Sitan (chief deity of the lower world) was assisted by many mortal agents. The most wicked among them was Mangagauay. She was the one responsible for the occurrence of disease. She was said to possess a necklace of skulls, and her girdle was made up of several severed human hands and feet. Sometimes, she would change herself into a human being and roam about the countryside as a healer. She could induce maladies with her charms.”

3. The third they called MANYISALAT, which is the same as mangagauay. These priests had the power of applying such remedies to lovers that they would abandon and despise their own wives, and in fact could prevent them from having intercourse with the latter. If the woman, constrained by these means, were abandoned, it would bring sickness upon her; and on account of the desertion she would discharge blood and matter. This office was also general throughout the land.

– Today we believe Manyisalat may have been considered another malevolent deity by early Tagalogs. She was the second agent of Sitan, tasked to destroy and break every happy and united family that she could find.

– No distinction as a witch exists today.

4. The fourth was called MANCOCOLAM, whose duty it was to emit fire from himself at night, once or oftener each month. This fire could not be extinguished; nor could it be thus emitted except as the priest wallowed in the ordure and filth which falls from the houses; and he who lived in the house where the priest was wallowing in order to emit this fire from himself, fell ill and died. This office was general.

– We believe now that Mangkukulam may have been another malevolent deity to ancient Tagalogs. The only male agent of Sitan, he was to emit fire at night and when there was bad weather. Like his fellow agents, he could change his form to that of a healer and then induce fire at his victim’s house. If the fire were extinguished immediately, the victim would eventually die. His name remains today as witch

– A “witch” Mankukulam is a person employing or using “Kulam” -a form of folk magic practised in the Philippines. It puts emphasis on the innate power of the self and a secret knowledge of Magica Baja or low magic. Earth (soil), fire, herbs, spices, candles, oils and kitchenwares and utensils are often used for rituals, charms, spells and potions.

5. The fifth was called HOCLOBAN, which is another kind of witch, of greater efficacy than the mangagauay. Without the use of medicine, and by simply saluting or raising the hand, they killed whom they chose. But if they desired to heal those whom they had made ill by their charms, they did so by using other charms. Moreover, if they wished to destroy the house of some Indian hostile to them, they were able to do so without instruments. This was in Catanduanes, an island off the upper part of Luzon.

– We think that Hukluban may have been considered the last agent of Sitan and could change herself into any form she desired. She could kill someone by simply raising her hand and could heal without any difficulty as she wished. Her name literally means “crone” or “hag.”

– Today, the Hukloban is also considered a “witch” who could kill anyone simply by pointing a finger at him and without using any potion. It could destroy a house by merely saying so. The Hukloban appear as a very old, crooked woman.

6. The sixth was called SILAGAN, whose office it was, if they saw anyone clothed in white, to tear out his liver and eat it, thus causing his death. This, like the preceding, was in the island of Catanduanes. Let no one, moreover, consider this a fable; because, in Caavan, they tore out in this way through the anus all the intestines of a Spanish notary, who was buried in Calilaya by father Fray Juan de Merida.

– Today, Silagan are considered “witches” in Catanduanes who preys on anyone who is dressed in white. They tear the liver and eat it afterwards.

7. The seventh was called MAGTATANGAL, and his purpose was to show himself at night to many persons, without his head or entrails. In such wise the devil walked about and carried, or pretended to carry, his head to different places; and, in the morning, returned it to his body – remaining, as before, alive. This seems to me to be a fable, although the natives affirm that they have seen it, because the devil probably caused them so to believe. This occurred in Catanduanes.

– Today we know this creature as the self-segmenting Manananggal. There are similar myths of creatures with almost exactly the same features throughout SE Asia. In Malaysia it is called the Penanggalan (Penanggal). In Thailand it is called the Krasue, in Laos it is the Kasu or Phi-Kasu and in Cambodia it is the Ap. According to the folklore of that region, it is a detached female head capable of flying about on its own. As it flies, the stomach and entrails dangle below it, and these organs twinkle like fireflies as the Penanggalan moves through the night. It preys on pregnant women with an elongated proboscis-like tongue.

8. The eighth they called OSUANG, which is equivalent to ” sorcerer;” they say that they have seen him fly, and that he murdered men and ate their flesh. This was among the Visayas Islands; among the Tagalogs these did not exist.

– In the Visayas there are many classes of Aswang (click here to see the classifications). Some think this was an invention of the Spanish, but I don’t. I say this because it is not an unusual being to exist in the minds of societies evolving from animists beliefs and from the same migration as the people of the Philippines. Malaysia has the Raksaksa – humanoid man-eating demons, often able to change their appearance at will. The Indonesian Leyak are said to haunt graveyards, feed on corpses, have power to change themselves into animals, such as pigs, and fly. In normal Leyak form, they are said to have an unusually long tongue and large fangs. In daylight they appear as an ordinary human, but at night their head and entrails break loose from their body and fly (also similar to the above mentioned Manananggal). Most of the belief in these beings stem from the introduction of Hindu demons (asura) being absorbed into animist beliefs.

9. The ninth was another class of witches called MANGAGAYOMA. They made charms for lovers out of herbs, stones, and wood, which would infuse the heart with love. Thus did they deceive the people, although sometimes, through the intervention of the devil, they gained their ends.

– Today the Gayuma is known as a Filipino love spell to help the love lives of those with lonely or broken hearts.

– No distinction as a witch exists today.

10. The tenth was known as SONAT, which is equivalent to ” preacher.” It was his office to help one to die, at which time he predicted the salvation or condemnation of the soul. It was not lawful for the functions of this office to be fulfilled by others than people of high standing, on account of the esteem in which it was held. This office was general through- out the islands.

– Today we know that a Sonat was essentially like “bishop” who worked under the Catalonans and Babaylans.

– No distinction as a witch exists today.

11. The eleventh, PANGATAHOJAN, was a soothsayer, and predicted the future. This office was general in all the islands.

– I have not been able to find any additional information about the Pangatahojan. No distinction as a witch exists today.

12. The twelfth, BAYOGUIN, signified a ” cotquean,” a man whose nature inclined toward that of a woman.

– Ignorance at its finest. The Spanish certainly left their mark with this one.

Spanish documentation is littered with examples of how they abused their power over the people and stripped them of their beliefs in deities. They destroyed the village structure that circled around the babaylan, but they did not have as much success in dispelling the belief that folkloric spirits were responsible for everyday ailments and misfortune. Comparative studies with surrounding countries indicate that the concept and practice of what we could call “witchcraft” existed in the precolonial Philippines, but the most popular names for these beings in Philippine Folklore, particularly among the Tagalogs, may have come from the displacement of deities into the realm of superstition. Their ‘mortal agents’ are what remains.

SOURCES:

Customs of the Tagalogs (two relations), Juan de Plasencia, O.S.F.; Manila, October 21, 1589

Outline of Philippine Mythology, F. Landa Jocano, Centro Escolar University, 1969

Witchcraft, Filipino Style, Nid Anima, Omar Publications, 1978

The Creatures of Philippine Lower Mythology, Maximo Ramos, Phoenix Publishing, 1990

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.